The Artistry of Frustration

By Rene G. Cepeda

This article was originally published on Rene G. Cepeda’s website on July 24, 2015. It has been edited for visual consistency.

Recently I have been going through two very interesting games, Dark Souls and Bloodborne, designed by game-maker Hidetaka Miyazaki. These are often cited as prime examples of great video game design, lauded for their often times punishing difficulty and obscure and ambiguous yet intriguing storyline. While both games share mechanics and themes such as cycles of life and death and growth through perseverance and personal hardship, the framing in both is different enough to be considered an alternative exploration of these themes instead of simple repetition.

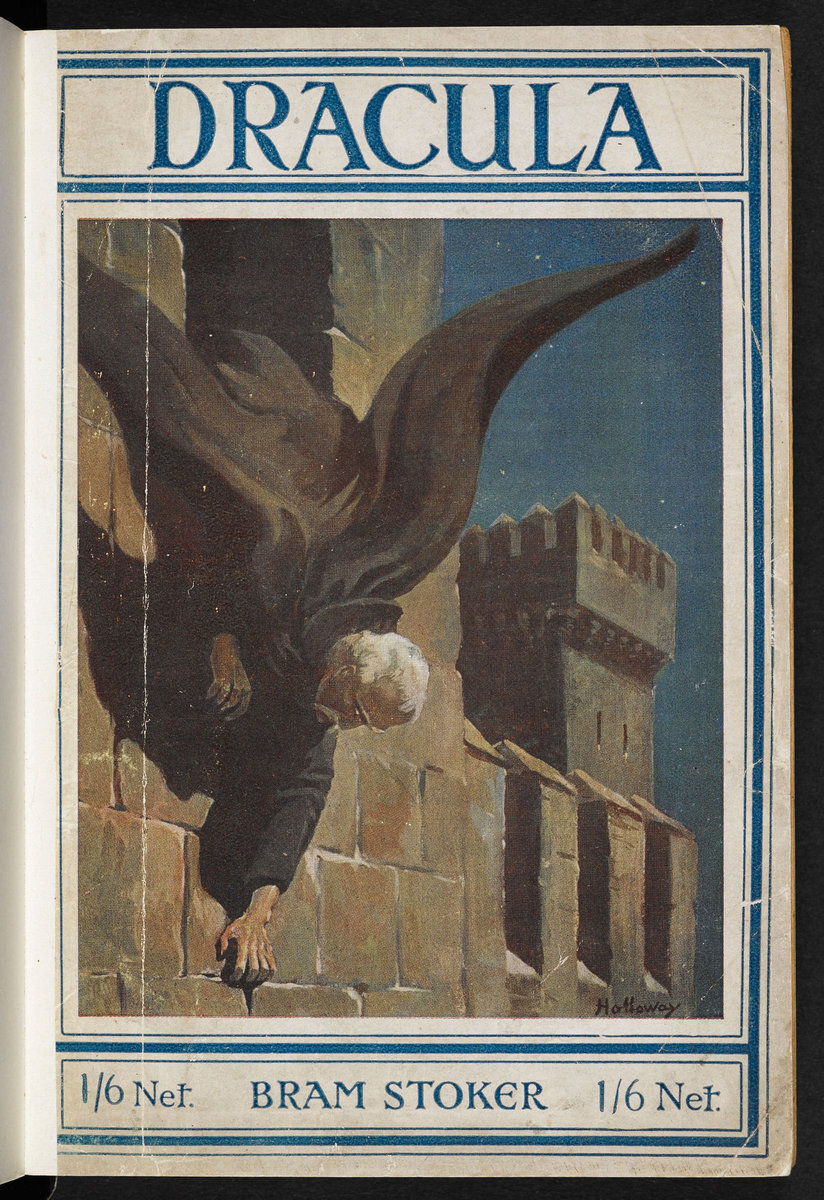

Visually both games are masterpieces of ambiance, design and art style. It is obvious Miyazaki drew inspiration from works of art such as Reubens’ Massacre of the Innocents and Goya’s Black Paintings, particularly Saturn Devouring His Son. While the purpose of this text is to talk about the artistry behind Miyazaki’s use of game systems to deliver a concrete message, it is impossible to not talk about the games’ classical, almost picturesque qualities. With a dark palette and a medieval tone, Dark Souls resembles a grittier (if that’s even possible) take of classical medieval myths. The angry giant, the tragic knight, dragons, wyverns, and more, serve as grounding to a world that is both beautiful as well as crumbling. Ruins and corpses litter the world yet their placement is not random, each one of them tells a story linked to the game itself, some act as warnings, while others add layers to the game’s plot and backstory. Meanwhile Bloodborne takes the gothic horror aesthetic of the 19th century, and mixes it with imagery and elements of Lovecraftian horror to create a world that resembles a mix of the 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which itself is a highly stylised take on the gothic theme, and the French film le Pacte des loups (2001)

As we can see Miyazaki and his team have a great eye for composition, technique and a masterful grasp of what makes Victorian horror so enthralling and timeless. I could dedicate an entire series to the artistry of Miyazaki’s visuals and his ability to capture past artistic achievements such as Ruskin’s Nocturnes, Goya’s historical paintings, and other influences and turn them into completely original works. However I believe that one of the most ignored facets of the video-games-as-art argument is the use of game mechanics as an important part of what makes a video game art. In this particular case I want to talk about the use of difficulty as a way to not only communicate to the player the general mood of the game world, but to also make a comment on how overcoming failure can be a reward on its own regardless of how the world continues to pile on.

Dark Souls, 2013

If I was asked to explain the appeal on either the Dark Souls series or Bloodborne, the first thing I would say is, ”You die, you die A LOT!” The screenshot above probably makes up for at least 3 hours of my life at this point, however this description is incomplete unless I add that when you finally succeed and defeat whatever has been obliterating you over and over again, the feelings experienced are incredibly powerful. On the surface it would appear that success in a video game could be this intense, however this seems to be the main attractor to the series, with customer and critic reviews consistently praising the difficulty and the sense of reward achieved.

Nevertheless difficulty in this game is spoken of in vague terms. What does it mean for a game to be difficult? How we interpret difficulty is a complicated proposition. The Oxford dictionary defines it as:

needing much effort or skill to accomplish, deal with, or understand

characterized by or causing hardships or problems

(of a person) not easy to please or satisfy

However this still too vague when we deal with video game systems. Difficulty in video games is a complicated concept, not only has the game to challenge and require skill, but the player should be able to overcome this hardship. Some games like Battletoads or Silver Surfer became infamous for their ridiculous difficulty. In Silver Surfer for example, one hit killed the protagonist, touching walls did the same, and the game was filled with enemies and hard to see bullets, everything in its design was antagonistic, even the design choices limited the player, colour schemes made it hard to determine what was a safe path and what was a barrier, movement was limited to four directions with no diagonals possible and finally the constantly scrolling screen made errors be fatal, the only solution was rote memorisation, there was no space for creativity or player interaction, everything had to happen in the single predetermined way the developer intended it. Now if we move over to Dark Souls, we notice something: the player can be killed by even the lowliest of enemies in one hit even if he is vastly more powerful, generally if there are more than 2 enemies attacking at the same time, the player is almost guaranteed to lose and the very environment can cause the player to fall and die in the most infuriating of ways. Not only that but upon death the player is deprived of his currency, his gear becomes less effective and his health is reduced.

At first glance it would appear Miyazaki’s games are just as punishing if not more than Silver Surfer. However the way the challenges are presented to the player shift this into a genuine challenge that the player can overcome. How Miyazaki achieves this is truly wonderful and demonstrates a deep understanding of visuals, human nature and a management of fear. Let us then address each one of my previous criticisms of Silver Surfer as they pertain to Dark Souls and Bloodborne.

One-hit kills

Notice how the enemy’s attacks can be properly anticipated and avoided.

A one-hit kill as the name indicates occurs when the enemy successfully connects an attack with the player and death occurs instantly. In Silver Surfer and other bad games these kind of attacks tend to be indistinguishable for attacks that are not instantly lethal (if they even exist in the game in question). In Bloodborne (as it is the most recent Miyazaki game, from now on unless otherwise specified Bloodborne will be used as the main example) all attacks can be anticipated through movement telegraphing. This concept know to martial artists and boxers simply as telegraphing occurs when the opponent’s motions anticipate an attack. Some boxers for example might lower the arm they plan to use to deliver an uppercut instead of keeping their hands up, Muay Thai boxers might look at the other boxer’s legs when they intend to deliver a low kick. In Bloodborne by design every attack that proves instantly lethal is heavily telegraphed, this reduces the unfairness of one-hit kills and encourages the player to observe and learn, not only that but once the movement is anticipated and the enemy committed, it is possible to avoid the attack, not only that, but it opens up the enemy to a retaliatory attack, creating a reward feedback where successfully avoiding an attack allows the player a small tactical advantage as opposed to just being allowed to continue playing.

Hostile Environment

Touching anything not coloured brown here will result in instant death.

In Silver Surfer, the game world is out to get you, touching a wall, a ledge, anything, means instant death. In Bloodborne, a misstep, an accidental dodge, even being hit can mean being flung into a chasm and often dying. At first glance both are incredibly unfair, there is however one slight difference, in Silver Surfer, knowing what is lethal is often a matter of trial and error, and error means starting over again. Not only that but the screen is actively scrolling down meaning there is no time to truly avoid mistakes. Bloodborne however allows the player to choose when and how to engage enemies, take the environment at their own pace. It is still a highly problematic part of the game, the controls are not really geared for delicate maneuvering, however the fact that the game world can be navigated at the players leisure reduces the frustration factor. Finally Miyazaki offers subtle visual and game building cues to inform the player about upcoming danger. For example, cliff areas may have some smaller non lethal drops to warn the player about the dangers soon to come and in any case most falls tend to not be lethal and might instead punish the player by forcing him or her to find their way out of wherever they landed. The overarching theme seems to be on punishing brashness and carelessness rather than being frustrating for the sake of being difficult.

Where Things Change

As I mentioned before, Dark Souls and Bloodborne do not punish the player for not having machine like performance, instead each death, is a learning experience, provided the player observes and learns from his or her mistakes, the next time, this death will not be repeated. However death is not without its consequences, each death costs the player humanity (how much health the character has) as well as souls (a resource used to buy items, repair armour and raise fighting stats) discouraging recklessness and repeated deaths to exploit the reward systems. It is a carefully crafted system that teaches players the values rewards and satisfactions of perseverance, hard work, careful thought and acting at the right time.

Difficulty as Art

“You may encounter many defeats, but you must not be defeated. In fact, it may be necessary to encounter the defeats, so you can know who you are, what you can rise from, how you can still come out of it.”

― Maya Angelou

In the Aristotelian sense Bloodborne teaches us temperance, to make the right choices, to be patient and only to act when the moment is right. Patience is a particularly important part of both Dark Souls and Bloodborne specially because in this particular case it draws from Aquinas’ interpretation of the term as suffering to receive something. Therefore we must suffer through the attacks of the enemy, spend precious time waiting and only attacking once the enemy has taken a rash movement. Very few other artistic mediums could teach this lesson as effectively as video games. In The Death of General Wolfe we might see Wolfe’s pain and death after the Battle of Quebec, yet we do not see his actions and his success, instead the artist presents us the end of the action, suffering is the predominant emotion on display, and while Wolfe is certainly presented as a tragic christ figure, the viewer does not experience the full range of emotions someone as Wolfe experienced. In film we experience the journey of a character or group of characters, yet the journey remains theirs, in Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925) we witness the hardship and battles the crew of the ship face, we empathise with them, and for a moment we might understand what drove them to action. In video games, we embody the characters, their struggle is ours, both failures and successes acquire meaning as they are shared experiences.

But even in video games the easy path can be taken, some video games reduce the challenge in its systems in order to enable the vast majority of players to be able to experience the game in question to its fullest. This in and of itself is not a detrimental quality, Gone Home has absolutely no combat or challenges, yet it is able to deliver a strong and poignant story of sibling love and the struggles of a gay woman coming out to her family. However in the cases where combat is evolved, when challenge is reduced, the result is a power fantasy, a ludic Mary Sue (a protagonist that is always in the right place and time and possesses all the right skills), and no message can be delivered as urgency and consequence get swept under the need to make the player feel empowered and valued. Miyazaki’s games defy these trends and deliver us an avatar that is vulnerable throughout the entire journey and whose success is not dependant on the accumulation of material goods but in personal growth. The art form reifies all the abstract feelings and concepts that other works of art attempt communicate. Not only that but this difficulty is intertwined with the plot and themes of the game. The loss of souls and humanity are linked to the story telling device of the undead plague the character suffers from and that is attempting to end, the one hit kills are explained by a world where injury functions in a closer way to our own. The difficulty is thematic as well as systemic therefore adding a layer of meaning to the challenges faced. Other games have been presented challenging combat, see Ninja Gaiden, others have attempted to tell stories that challenge the macho idea that a game has to be a power fantasy, Spec Ops: the line, to my knowledge only Miyazaki’s games have attempted both and done so in such a meaningful way.

It is for all the reasons previously expressed that I propose we consider the use of video game difficulty as an artistic quality in critiques when it is used effectively in conjunction with other more traditional artistic qualities such as craft, story telling, game making, etc. The creation of a game mechanic that not only delivers entertainment, but also a message and a moral lesson is to be praised and encouraged, but only if they manage to achieve the satisfying mixture of challenge and reward that goes beyond the spectacle and wiz bang of mainstream games to something with meaning.